Chinese Eco-Cities: viable environmental solutions or bold projects with no real future?

The term “eco-city” seems like the combination of two words that couldn’t be more unrelated to each other. Cities as we know them are far from being ecological: grey sky, polluted water and rare green spaces definitely do not match “ecological” definition on the dictionary. Add to the equation the word “Chinese” too and you get what sounds like a plain and simple oxymoron. The air in nearly all of China’s cities is harmful to breathe, half the drinking water is below international standards, and 20 to 40 percent of the arable soil is contaminated with toxins. However, Chinese eco-cities are a thing – at least on paper.

According to a 2009 World Bank report, China has launched over 100 eco-city projects in the last decade, more than any other country worldwide. These initiatives are part of Beijing efforts to tackle two of the most prominent of Chinese environmental issues – heavy pollution and uncontrolled urbanization. Once completed, the eco-cities should run on renewable energy, recycle their water and waste, have resource-efficient buildings and extensive public transportation networks.

Unfortunately, most of these projects will probably never see the light of day. The most (in)famous cases are Dongtan and Huangbaiyu projects. The former should have transformed an uninhabited grassy island near Shanghai into a visionary and futuristic city, housing up to half a million people. According to the original timetable, the first phase of construction was to be completed by the Shanghai Expo in 2010, thus allowing the municipality to show its commitment to a green future. Today, almost nothing has been built and the only construction that stands out is a visitor centre that is now shut.

Another failure was the Huangbaiyu project, which aimed at transforming a small village in North East province of Liaoning into a energy-efficient community. Although it managed to complete 42 homes by 2006, only a handful of these were built with the highly touted “ecological bricks”, made in special hay and pressed-earth. Besides, most of the houses remained empty, as cost overruns made the homes unaffordable to many villagers. In other instances, the farmers refused to live in them because the yards weren’t large enough to raise animals. On the plus side, the houses were built with a garage, although most of the villagers don’t own a car.

Both the eco cities were designed by internationally renowned foreign architectural firms and the launch of the projects had been widely covered by international media. So why did these plans not come to fruition? In the case of Dongtan, firstly it wasn’t clear whether the project was to be funded by Chinese government or by the foreign firms who designed it, so the construction came to a standstill. Secondly, the political leaders who championed the plan were ousted in a corruption scandal and the project definitely stalled. In the case of Huangbaiyu, on one hand there was a lack of oversight: no one ensured the plans on paper could be effectively translated into projects on the ground; on the other hand, the eco-city didn’t adapt to local circumstances and needs, resulting unappealing to the village community.

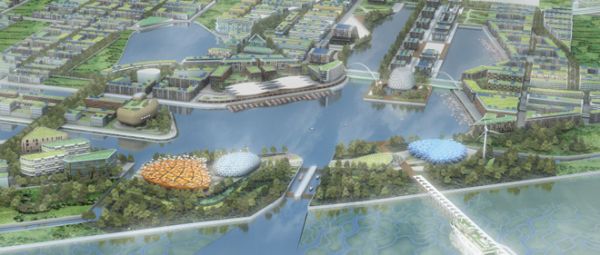

Despite the failure of these first attempts, not all of Chinese eco-cities seemed to be destined to encounter the same fate. Standing out among the multitude of eco-city proposals is the Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-city project, which seems to have learned some lessons from the mistakes of its predecessors. The plan, resulting from a partnership between the Singapore government and Tianjin local government, looks promising for different reasons. On one hand, the position is highly strategical: located within the fast growing economic hub of Tianjin Binhai New Area, some 40 km away from Tianjin city center and 170 km from Beijing, it is more likely to attract further investments. On the other hand, the project is funded by both sources and is expected to have significant economic returns, making a greater level of supervision and follow-through more likely. In order to encourage people to move there, government and investors’ incentives made rents and other services, such as school tuition costs, much cheaper than in central Tianjin. On paper, the plan seems overall to be proving successful so far: the first goal set by the developers – to cover 3 sqm by 2013 – has been met and the buildings comply with the world’s most stringent green architectural standards. Unfortunately, despite all the efforts, they stand mostly empty and unused. The problem probably lies in the project of building a whole new city from scratch rather than letting it develop organically: it may work on the drawing board, but it’s harder to actually implement it. At present, Tianjin eco-city doesn’t have any hospitals, many storefronts on its main shopping plaza stand empty and most viable employers are at least half an hour away by car. Construction is everywhere, but the people are scarce.

If Tianjin eco-city doesn’t manage to attract more inhabitants in the next few years, its fate may be the same as Dongtan’s and Huangbaiyu’s: a bold futuristic vision that couldn’t translate into reality. There is still hope – the project didn’t stall and it’s still building after all – but chances are that “Chinese eco-city” may just remain a fascinating oxymoron and nothing more.

china, Dongtan, eco.city, featured, futuristic city, green, Liaoning, natura, shanghai, Tianjin, Uomonatura1, urbanization