China and the West: a love-hate relationship

Almost one million people have already visited Shanghai Disneyland – quite an impressive number considering that the park isn’t even technically open yet. Since the Shanghai Disney metro station opened its doors on April 26th, thousands of tourists have rushed to it just to stand outside the gates of the unopened park and buy souvenirs.

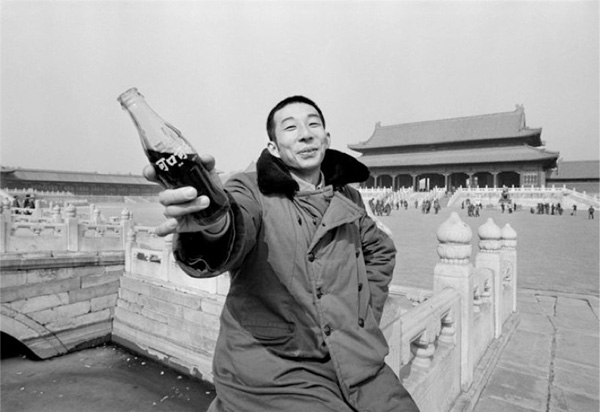

This episode is the last of a long series of examples of China’s obsession with Western symbols and products. Since the XIX century, China’s conception of the West has in fact been characterised by a constant tension between attraction and antagonism, admiration and criticism. After the years of China’s isolation under Mao’s rule, when Westerners were depicted as yang guizi (foreign devils) and nearly no visitors were allowed in the country, in 1978 Deng Xiaoping launched the “open door policy”, making China accessible to foreign businesses that wanted to invest in the country. This policy set into motion the unprecedented economic growth of modern China, resulting in immense changes in Chinese society.

One of those changes was the increasing fascination with everything “Western”. In the 90s, when the reforms deepened and accelerated, it was not unusual to hear salesmen in city markets across China describe pretty much all of their merchandise as “made in America”.

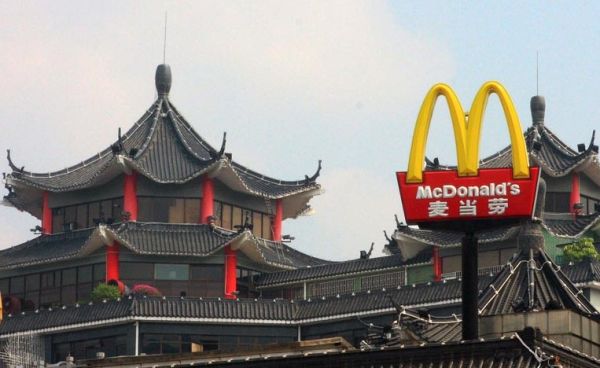

The tremendous potential of the Chinese market caught the attention of Western restaurants and commercial chains, which started opening branches in the country. One of the first to tap into this potential was McDonald’s, which in April 1992 inaugurated a store in the heart of Beijing, just two blocks away from Tiananmen Square. With 28,000 square feet, 700 seats and 850 total employees, it was the chain’s largest store in the world, clearly testifying to the company’s determination to invest in the Chinese market.

Although at that time a 10 yuan Big Mac was not affordable for most of the population – the average monthly salary of urban residents of Beijing amounting to 120-130 yuan (around 17-18 dollars) – many Chinese still flocked to the store. Thanks to its Western appeal, its cleanliness and quick service – in sharp contrast to the poor standard of service long endured by customers at local restaurants – McDonald’s soon became a common family hangout spot, as well as a popular place for first dates.

Thanks to the increasing knowledge of Western culture made possible by the widespread of Internet across China, Chinese people nowadays aren’t as blindly in love with the West as they were during the Reform era, but they aren’t immune to its allure either.

Just consider that in 2015 over 520.000 Chinese students moved abroad to study, with Western countries such as the US, the UK and Australia being the most popular destinations, followed by South Korea and Japan.

Even Western TV shows, in particular American ones, have become increasingly popular in China in the last few years. One example is the Netflix drama “House of Cards”, which is so in vogue that it has inspired many fan-made parodies, including this version of the credits sequence featuring Beijing rather than Washington.

But what does the Chinese government think of its people’s long-lasting fascination with the West? The answer is not straightforward. Despite continuing to support the open door policy, after the violent repression of Tiananmen protests in 1989, Deng Xiaoping’s administration launched the Patriotic Education Campaign with the slogan “Never Forget the National Humiliation”.

Since then, student textbooks as well as radio programs, TV shows and movies have been nurturing anti-Western nationalism among Chinese people, by depicting the country as a victim of foreign powers that exerted control over China for a hundred years, until the Communist revolution in 1949. This rhetoric champions the Communist Party as the guardian of the country’s safety and aims at justifying its one-party rule.

As a result, China is extremely sensitive about any kind of Western interference in its internal affairs, as demonstrated by people’s angered reactions to Western criticism of China’s human right abuses in Tibet.

Moreover, in the last few years anti-Western sentiments have intensified. In 2012, following the episode of a Chinese woman harassed by a British expat, top Chinese search engine Baidu and the Twitter-like microblogging site Sina Weibo both called on netizens “to expose bad behavior by foreigners in China” leading many users to express xenophobic views, such as “foreign scumbags should go back to their countries”, as microblogger Yuxiaolei stated, or “cut off the foreign snake heads”, as popular television host Yang Rui wrote.

In 2015 Chinese education officials intensified a campaign against so-called Western values and professors at Chinese universities complained that they were being pressured to remove foreign material from their syllabus.

Finally, just last month cartoon posters in Beijing entitled “Dangerous Love” warned young female government workers against dating Western men, as they may turn out to be foreign spies.

Given the backlash against foreigners of the last few years, it is difficult to predict how China’s love-hate relationship with the West will unfold in the future. Let’s just hope that burgers and tv shows won’t be the only reasons left to Chinese people to admire the West.

Cover Photo: Castel of Shanghai Disneyland by Fayhoo (CCA-SA 3.0/Wikimedia Commons)

burger, china, deng xiaoping, featured, house of cards, mac, mao, mc donald's, Occidente1, open door policy, shanghai disneyland, westener, yang guizi