“Tomorrow I’ll try again!” Ahmed’s story

We are quietly seated around a table and Ahmed decides to tell us his story in detail. He comes from the South of Somalia and his city of origin is a few kilometres away from the borders of Ethiopia and Kenya. His family – father and mother, two sisters and a little brother – are still there, waiting for Ahmed to reach his destination. He is the eldest son, and is sixteen years old. He talks raising his head and large eyes and articulating his sentences in a sharp English. He wears his red hat, the one he reserves for special occasions, the one he wouldn’t wear when sleeping on the station floor, waiting to cross the border.

A soft music, played on a smartphone, is Ahmed’s background as he plunges into his memories. He used to go to school in Kenya, then the border was closed and militarised, so the possibility of having an education was precluded to him. He then attended for around a year an unofficial school – which the best part of his community didn’t approve of (“but one day on the street my friends told me: come to school, the teacher is good, very good!”) – set up by a man who payed the rent for the rooms they used for the classes himself. The classrooms where positioned in different areas of the city so as not to be located, but they guaranteed access to education. This person, who strongly believed in education and its power to take boys away from war, became his teacher: there were two classes to which students could be assigned depending on their level of knowledge (“young” and “old”) and a number of subjects were taught (English, Arabic, maths, chemistry, IT…). From time to time Ahmed helped his teacher, teaching the students of the “younger” classes, even though some of them where older than him.

The terrorist group Al-Shabaab had been threatening the teacher for some time, blaming him for taking boys aways from military training and for teaching unapproved subjects (such as the English language). The teacher decided to inform Ahmed of what was happening, letting him know what the risks were, and the situation went on like that for around a year: threatening phone calls, death threats, increasingly serious intimidations. Ahmed tells us that the biggest difficulty in his town is that terrorists are everywhere but unrecognisable. “They are part of the population. You would be talking to a woman, and she would fall dead before your eyes without you knowing how or by whom she was murdered. There were often stray bullets and improvised hails of stones”.

One day the teacher asked Ahmed to teach to one of the younger classes while he went to teach to another classroom. The evening before terrorists had threatened him again.

Ahmed completed his task, something he had already done a number of times. But this time terrorists broke into the classroom and killed the teacher in front of his students. “I knew I was going to be the next one… I was in their sight, they would have come for me too”. As soon as Ahmed was informed of his teacher’s murder, he organised his departure with the support of friends and relatives, and in three days he collected 3,000 dollars. He fled his community heading towards the border. He managed to bypass a checkpoint and, after avoiding contact with soldiers, he found himself in Kenya. This was in March 2016.

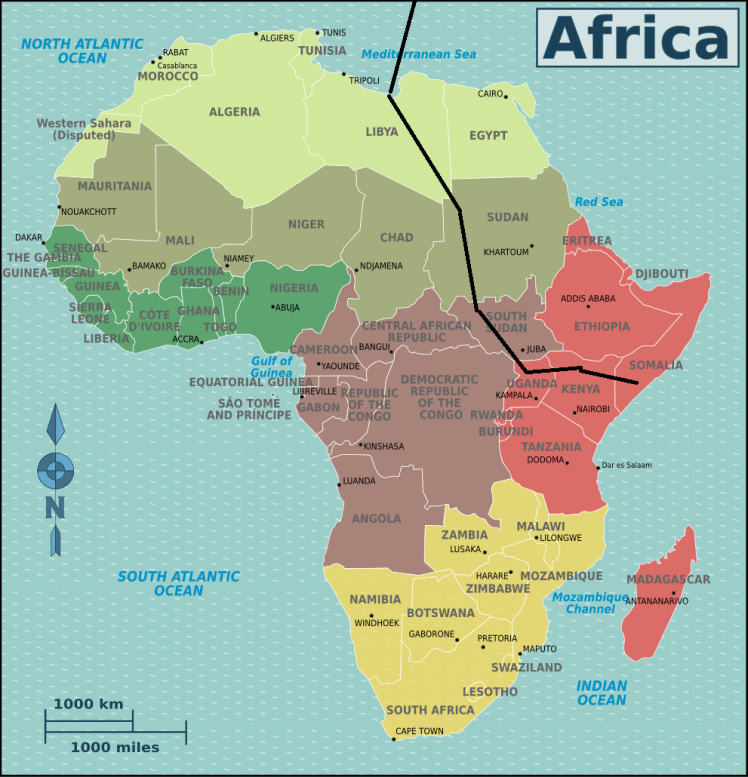

“When I got to Kenya I had to look for a smuggler who would organise a series of passages through African borders and my arrival in Libya. It didn’t take long, I showed him what money I had and he said I would have had to pay at the end of the journey”.

He crossed Uganda as the only passenger on a Toyota pick-up. “At every border crossing we changed driver and increased in number”. They departed from South-Sudan in six, in Sudan more people joined them and they headed towards the Saharan desert.

The journey across the desert lasted eight days: they were twenty-four and they had a proper break only on the fourth day. (“It was very hard. It was unbearably hot and they gave us water only once in a while. From time to time we stopped to sleep on the roadside”).

After five more days of walking – it was May by now – he arrived in Libya, where he was taken to a prison in the suburbs of an unknown city. “They made me and many others go through a corridor… they said ‘You are from Somalia, it’s 6,000 dollars. Do you have the money?‘ I said I only had 3,000 dollars, but they insisted so I replied: ‘I don’t have 6,000 dollars’ and then they said ‘Ask your family for help! We have a trusted man close to them and they could give us the money to save you from prison’. And I said ‘I know my family, they don’t have the money. Do as you please, beat me, kill me, but we don’t have the money’ ”. He relays this dreadful conversation with astonishing naturalness.

Conditions were extremely difficult and there was very little water (“They would give it to us once in the morning and once in the evening, because they said that otherwise we would have used the toiled too often and guards would have wasted time checking on us”).

He stayed there for four months enduring continuous mistreatments (“They came every day asking us for money and every day I replied I didn’t have it”), until he was released without explanation. Ahmed tells us that there are many refugee camps in Libya, which are controlled by the local armed militias. As soon as he was released from prison, he was held in one of such camps for months. The situation was definitely better if compared to that in prison, but here too guards threatened refugees with guns. “There were loads of people, boys, men but also women who were pregnant or with young children”.

He then waited to be told when to set off to cross the sea. “ ‘You! Stand up. It’s time to go.’ And, with a shotgun pointed to my back, I stood up and went right off”. It was November.

They reached the jetty in two-hundred, and then increased enormously in numbers, up to between six-hundred and eight-hundred people. Traffickers filled to the limit all three levels of the ship, showing “passengers” where and how to sit. “We were packed liked cookies in a box. Perfectly sat one next to the other, so that we couldn’t move. I sat hugging my knees with my arms. Like cookies in a box.”. He repeats this metaphor a number of times, miming the peculiar puzzle of people, and assures us that they all remained in the same position for more than six hours. Ahmed was in the back of the ship, on the lower level, in one of the most dangerous areas. He tells us about the fear, the whispered prayers and the quiet crying. This situation lasted until a team of Doctors Without Borders came to their rescue, then cries of joy erupted after a long silence: “We are safe! We are safe!”. When the first rescuers came to the level where he was held, Ahmed discovered where they were and what their direction was: “We didn’t know where we were directed, not even what city we were in. In that moment I discovered that the final destination was Italy, and that I was about to arrive to Trapani” [Sicily] ). The journey on the boat of Doctors of The World lasted two and a half days, during which migrants received medical, legal and psychological support, as well as the announcement that upon arrival reception staff would be obliged to take their fingerprints, as per the Dublin Convention.

This is what happened next: after being moved to a reception centre in Trapani, Ahmed’s fingertips and his mugshot were taken. He remained there one night, and the next day he was taken to Chianciano Terme, in the area around Siena (Tuscany). There he discovered he had scabies on his hands, and, after being examined by a doctor, he was given a treatment based on creams.

Once the condition had been treated, he entered a centre, but after a couple of weeks he restarted his journey: after many difficulties he arrived to Ventimiglia (a city in Liguria, on the border between Italy and France). He says he has a friend in France, he doesn’t know exactly where because they are not in touch, but he hopes to find him sooner or later. “For me it’s very important to get to France… have you ever heard about the education system they have for refugees? I was told it’s very good […] My ideal job is that of IT specialist… or programmer… or IT engineer, anything to do with technology!”

Since he arrived in Ventimiglia, Ahmed has tried to cross the border twice: he is underage and it is his right to ask humanitarian protection in France. French policemen don’t seem to agree on this point, and the second time he attempted to enter the country they returned him to Italy with an expulsion order that included false information: “They wrote down a different name from mine, I told them that those were not my personal details but they didn’t want to hear it and they sent me back to Ventimiglia. One of the policemen told me that if he saw me again, if I even tried it again, he would beat me up. Another one whispered to my ear a suggestion on how to make it”. When we meet Ahmed for the first time, he is sleeping at the station. We give him a few blankets and our phone numbers, with the promise to talk again.

The next day we meet on the beach, it’s pretty warm for late December. We talk about his story, about how passioned he is about IT and languages – he speaks seven languages fluently. We write a few lines in French: “Je m’appelle Ahmed. J’ai seize ans et j’ai le droit de demander asile en France” (My name is Ahmed. I am sixteen years old and I have the right to seek asylum in France). Although probably useless, at least now he has this piece of paper to show the next time he is stopped and his desire to cross an imaginary line crushed.

We decide to give him hospitality so that he can recover, we prepare a risotto and laugh, we sing. We relax so that he can face calmly the journey he wants to try the next day. We explain to him that the route to Paris is risky: with the destruction of the Calais Jungle thousands of migrants poured on the streets and repression is strong. That’s the route he wants to try. “The French policeman whispered in my ear: take a bus! And this is what I’ll do. I have a couple of contacts, I can get somebody to pick me up at the station”. We buy bus tickets, as Ahmed only has 20 Euros left.

At the moment of departure he looks radiant with his hat on, he leaves at home everything that could weight him down during the journey and sets off (“You know, when you meet people like you… You see, you don’t want to go. You are the only ones who understand my situation, thank you”). We wait anxiously for him to get in touch. He calls us in the evening, after many hours, but not with good news. He didn’t make it this time either: in Niece, on the highway, there was a checkpoint and he was immediately discovered. He showed his paper with the French writing to the policemen but they didn’t even acknowledge him and they sent him back to Ventimiglia. When he calls us he is again at the station, and, giving him indications over the phone, we manage to direct him to a more welcoming place: he won’t spend this night sleeping rough either, but he is impatient and states firmly:

“I’ll try again tomorrow!”

Translated from Italian to English by Sara Gvero

Borders, featured, France, italy, Libya, migrant, migranti1, Migration, Refugee, somalia, Ventimiglia