Sina Weibo: better than Twitter? Not yet

Over the past few months a number of news outlets have claimed that the social network Twitter is dead, mainly due to the platform’s struggle to gain new members and make profits. Whether this is true or not – commentators have declared Twitter deceased pretty much every year since 2009 – what is certain is that another Twitter-like social media is definitely on the rise in China: Sina Weibo. With 222 million monthly active users in 2015 – 33% more compared to the same period the previous year – Weibo, as it’s commonly known, is one of the most successful and influential microblogging services in the Middle Kingdom.

Often referred to as “the Chinese Twitter”, the platform combines the functions of Facebook and Twitter, but it’s ultimately unique. Like Twitter, Weibo has a 140 character limit per post and the relationship between followers and followees is unidirectional: one can follow other users and read their weibo (posts), without being followed back.

Similarly to Facebook users, however, those on Weibo tend to disclose more personal information about themselves than most people do on Twitter. This is probably due to the fact that Weibo is much more user-friendly and offers a wider variety of features than its Western counterpart. For example, not only it is possible for users to upload rich media such as videos, images and gifs, but these can be viewed directly from one’s home timeline without the necessity of clicking on a link.

Another great feature of Weibo is threaded comment. While on Twitter users need to browse the @mentions to see what other people think about their tweets, Weibo’s threaded comments allow one to see all the comments made to their posts with just one click.

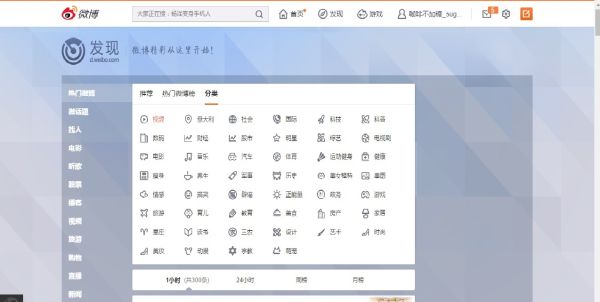

In addition to these Facebook-like features, Weibo also offers its users the possibility to check out the hottest trends on the platform. Unlike Twitter, however, the Chinese social network sorts these by several categories (sport, entertainment, finance, gaming, travelling, etc.), so that users can easily find what interests them most. Not only one can view the first 10 hottest trends by category at the moment, but these can also be tracked back by setting a specific date or timeframe for the search.

Finally, Weibo has introduced a medal reward system that encourages users to spend more time on the site. Medals can be won for interacting with people and brands or for meeting milestones, and each user has a page where they can see their (and other people’s) medals. While this may seem unnecessary at first glance, the system is actually part of Weibo’s business strategy. Brands such as Nike and Transformers actually partnered with Weibo to market their products by offering medals as rewards, which can be acquired by performing certain actions, like retweeting about their events.

Weibo appears to offer much more features than Twitter and it does so in a much more user-friendly way. So, what’s not to like?

Well, as usual all that glitters isn’t gold. Following the Chinese authorities’ ban of Twitter and Facebook after the Urumqi riots in 2009, Sina Weibo was introduced the same year as a new social media platform that would keep posts under control by tracking and blocking sensitive content. Basically, the platform automatically removes posts with specific words or covering sensitive topics.

As a result, in the past few years Chinese activists have come up with coded phrases to share information and criticise the state. For example, when a user account is deleted, Chinese activists say that the account has been “river-crabbed”. This word in Mandarin sounds like “harmonise”, so it aims at making fun of the government’s stated reason for censorship – to keep society “harmonious”. As the expression “Grass-mud horse” in Mandarin sounds similar to the phrase “f*** your mother”, you can deduce what the following post may mean: “Someone’s account has been river-crabbed. These people can grass-mud horse”.

The problem is that these phrases can remain undetected only as long as they don’t go viral. Once a phrase becomes popular, the censors crack down on it everywhere making it completely disappear from the platform and even deleting users accounts caught using it. For this reason, people now tend to use WeChat (an instant messaging app similar to American Whatsapp) for private conversations on human rights and political issues, even though some activists have recently claimed that their WeChat accounts have been deleted too.

Despite these issues, Weibo is known in China to allow more criticism of the government than other sites. Most of the Chinese users I’ve spoken to said that censorship on Weibo is limited to “false news” and that only accounts that actively contribute to spread them get deleted. It would make sense, I suppose, if one didn’t know that most of non-government-approved news are marked as “false”.

Censored or not, Sina Weibo is the first public social media platform in China and the country’s most dominant source of news content, where netizens come to acquire, share and comment news. Twitter could definitely learn a thing or two from it, but we do hope it maintains the censor-free spirit that has always characterised it.

Cover photo by webstershows (CCA-SA 4.0 Commons Wikimedia)

censorship, china, featured, twitter, Twitter1, Weibo